POULTRY INDUSTRY ASKS FOR LINE-SPEED INCREASES: The chicken industry has petitioned the Food Safety and Inspection Service to lift the speed limit on bird processing lines for some plants, setting up a clash with labor advocates who fear more injuries could result if the request is granted. Processing lines face a 140-bird-per-minute limit, but the National Chicken Council, in a petition dated September 1 but made public on Friday, asked for an exemption for plants that opt into the New Poultry Inspection System, a more rigorous food safety inspection program.The National Chicken Council wants participating plants to be given "the flexibility to choose to operate at appropriate line speeds based on their ability to maintain process control," according to the petition, which was addressed to Carmen Rottenberg, acting deputy undersecretary for food safety. In order to qualify for the exemption, the petition suggests plants also be required to take part in the Salmonella Initiative Program and establish a system for monitoring and responding to loss of process control.The chicken industry contends that faster speeds wouldn't endanger workers and would help maintain efficiency in light of increased inspection. It also said the change would incentivize more plants to participate in NPIS and serve to eliminate competitive barriers between the U.S. and international chicken producers. The industry argued that lifting the speed limit isn't as dangerous as it sounds because speed increases would primarily occur in areas of processing plants that are largely automated. "There are multiple safeguards in place to ensure plants continue to operate in compliance with federal worker safety requirements, regardless of the line speed at which they operate," the council said in the petition.Forty advocacy and labor groups, including the National Employment Law Project, wrote Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue last month in anticipation of the request, arguing it would worsen worker safety conditions in an industry already plagued with injuries. "Even at current speeds, poultry slaughter and processing workers face serious job hazards that result in debilitating illness, injury, or death," they said. "Indeed, workers in poultry plants are injured at almost twice the rate of workers in private industry." USDA told the council it's evaluating the request.

Ever since I was a small boy, I have been amazed at factory work. From the top down, from directing operations to the person working the line. What are the various parameters which have to be optimized in order to make an "processing" or "assembly" line run smoothly? A large part of that is dependent on the manufacturer's product -- what is either being "processed" or "assembled" to be shipped to either a store or the next stop in the production line? I am continually fascinated by the concept of 'high throughput'.

After reading the above excerpt from 'Politico Agriculture' I started thinking about the hazards associated with increasing the speed too much on the "processing" line at a Poultry processing plant. For one, the amount of inherent 'errors' which are made by each employee scales with speed. The faster a processing line goes, the more 'error' prone the workers are. That is, of course, after the optimal speed is reached. I imagine that the standard speed (safe speed) is set quite a bit below the optimal speed.

At the same time, the owners of the poultry processing plant have an investment in mind. Their main focus is high throughput of poultry. Get as many through to the customer is as humanly possible. This increases their bottom line and satisfies their shareholders (more profits).

How About The Labor Workers?

On the flip side of the requests made above, the opposition toward speeding up the processing line comes from the actual workers 'on the line.' Here is a letter from the National Employment Law Project along with advocacy and labor groups in opposition to the increase in speed:

Dear Secretary Perdue,

The following organizations write to strongly oppose any proposed rule that would increase line speeds in poultry plants within the United States above the current 140 birds per minute (bpm). We were alarmed by the recent letter from Congressman Doug Collins (GA) requesting an increase in the line speed to 175 bpm, and we take issue with many of the claims therein. Most significantly, we are deeply concerned that any line speed increase would jeopardize the health and safety of both poultry workers and consumers at large.

Even at current speeds, poultry slaughter and processing workers face serious job hazards that result in debilitating illness, injury, or death. Indeed, workers in poultry plants are injured at almost twice the rate of workers in private industry. These workers face over seven times the national average of occupational illnesses, such as repetitive motion injuries. And, as the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) noted, these rates are likely underreported.

Increasing the line speed by a full 25 percent to a shocking 175 bpm—or 3 birds per second—would only make a bad situation worse. This is evident for anyone who has visited a poultry plant. Workers stand, shoulder to shoulder, in cramped quarters, amid deafening noise and slippery conditions. They make thousands of forceful cuts a day at break-neck speed, using sharp knives and scissors, with acidic chemicals sprayed over the meat, and onto the skin, and into the eyes, nose and throat of the workers, as the meat moves down the line. A single wrong move could lead to an amputated finger or life-threatening cut. And cumulatively, these repetitive movements cause irreparable damage to the nerves, tendons, and muscles of the workers.

Despite Congressman Collins’ claim that production line speed is unrelated to worker health, experts are convinced otherwise. For instance, according to the Government Accountability Organization (GAO), “High line speeds resulting from increased automation and other factors may exacerbate hazards. . . .[L]ine speed—in conjunction with hand activity, forceful exertions, awkward postures, cold temperatures, and other factors such as rotation participation and pattern—affects the risk of both musculoskeletal disorders and injuries among workers.”

Two further studies from the National Institute for Occupation Safety and Health (NIOSH) confirm these findings. They reported staggeringly high rates of injuries directly related to the rapid, repetitive motions. In one study, 34 percent of workers had carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), and 76 percent had evidence of nerve damage in their hands and wrists. In another study, 42 percent had CTS. These numbers are not an unhappy coincidence. As NIOSH’s agency director stated, “Line speed affects the periodicity of repetitive and forceful movements, which are key causes of musculoskeletal disorders.” In other words, the faster the line speed, the greater the risk of harm.

It’s also clear that the line speed in poultry plants may pose dangers to consumers. OSHA citations show that workers are denied breaks, including breaks to use the restroom, in order to keep lines going at full speed. Many workers end up soiling themselves while standing on the processing line; this poses an obvious danger of contamination.

While Congressman Collins and others refer to higher line speeds in other countries, evidence points to clear problems. Germany allows line speeds up to 200 bpm in poultry plants; the country also experiences particularly high levels of Salmonella and Camplylobacter contamination in poultry meats, which is largely attributed to the slaughter process.

In a recent statement, Congressman Collins referenced positive results arising from pilot programs allowing line speeds to be raised from 140 to 175 bpm. No such outcomes can be found. In fact, the GAO strongly criticized the USDA for the lack of credible evidence emerging from the pilot program to support its claims that higher line speeds were safe for workers and consumers.9 Furthermore, data from the pilot programs found an average line speed of 131 bmp, far below the 175 permitted. And even with the 131 bpm line speed, the USDA recognized the dangers of higher line speeds to workers and noted that more studies would be needed before any increases be made.

It should also be pointed out that USDA researchers have found that the regulatory pathogen testing results in the pilot plants may have been skewed as the antimicrobial chemicals used in those plants probably overpowered the collection broth used by inspectors to collect samples. That may have led to the reporting of false negative results, understating the actual level of pathogens in the poultry. Consequently, USDA developed and began using a stronger neutralizing agent in its pathogen sampling program in 2016.11 Any food safety arguments made to increase line speeds using the track record of the pilot plants need to be viewed skeptically.

Finally, Congressman Collins argues that increasing line speeds is necessary to compete with German and Belgian factories, which operate line speeds of 200 bpm or more. However, Germany and Belgium are not permitted to export their poultry to the United States, so their industry standards have no impact in the U.S. market. Furthermore, as noted above, the poultry found in these foreign plants still has high levels of pathogens that continue to be of concern to European food safety officials.

In short, we urge you to reject any calls to increase poultry line speeds. The overwhelming evidence to date suggests this increase would have disastrous results. Until the USDA completes its studies evaluating the safety of existing poultry plant line speeds, no changes in standards should be proposed or made. Any move by the USDA to increase line speeds in poultry plants would be in complete disregard to the safety of the 250,000 working men and women who endure already exceedingly harsh working conditions to feed their fellow Americans.

Sincerely,

A Better BalanceAmerican Public Health Association, Occupational Health & Safety SectionBeyond OSHA ProjectBrazos Interfaith Immigration Network/Centro de Derechos LaboralesCenter for Science in the Public InterestCommunications Workers of AmericaConquista Interpreter ServicesDepartment of Public Health, UMass LowellEconomic Policy InstituteFe y Justicia Worker CenterFood & Water WatchInstitute for Agriculture and Trade PolicyInterfaith Worker JusticeInternational Brotherhood of TeamstersKnox Area Workers’ Memorial Day CommitteeKnoxville, Oak Ridge Area Central Labor CouncilKOL FoodsNAACPNational Council for Occupational Safety and HealthNational Employment Law ProjectNebraska Appleseed Center for Law in the Public InterestNew Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health PolicyNH Coalition for Occupational Safety and HealthOccupational Health Clinical CentersOEM consultantOxfam AmericaPhiladelphia Area Project on Occupational Safety and Health (PhilaPOSH)Presbyterian Church (USA) Washington Office of Public WitnessPublic CitizenPublic Justice CenterSafeWork WashingtonSargent Shriver National Center on Poverty LawSciencecorpsSouth Florida Interfaith Worker JusticeSouthern Poverty Law CenterUFCWUnidosUS (formerly NCLR)Western North Carolina Workers’ CenterWisCOSH, Inc.Worksafe

Workers in any environment deserve protection against cruel and inhumane conditions. History shows that the U.S. has exploited workers throughout time in various conditions. Over the last two centuries, the U.S. has made leaps and bounds to an extent on improving workers rights on a national level. Of course, this is no time to celebrate, there is plenty of work to still be done. Illegal immigrants whose work the U.S. depends heavily upon still find themselves subject to torturous conditions in various parts of our nation.

The stories typically do not make national headlines, because the majority of us would rather turn our heads than speak up in favor of making positive changes to promote the health of workers whose labor ultimately contributes to the health of the nation. Think about farmers, construction workers, industrial plant workers, and the beef and poultry industries whose labor is not all legal. Each deserve a higher quality of life -- even if that means that the business owner receives less revenue and the customer pays more for produce and meat at the grocery store counter.

Michael Grabell wrote an article for The New Yorker back in May of this year titled "Exploitation and Abuse at the Chicken Plant" in which he uncovers the problems of exploitation at large chicken farms and processing plants. Here is an excerpt below from the article describing the conditions each worker faces on a day to day basis:

Osiel sanitized the liver-giblet chiller, a tublike contraption that cools chicken innards by cycling them through a near-freezing bath, then looked for a ladder, so that he could turn off the water valve above the machine. As usual, he said, there weren’t enough ladders to go around, so he did as a supervisor had shown him: he climbed up the machine, onto the edge of the tank, and reached for the valve. His foot slipped; the machine automatically kicked on. Its paddles grabbed his left leg, pulling and twisting until it snapped at the knee and rotating it a hundred and eighty degrees, so that his toes rested on his pelvis. The machine “literally ripped off his left leg,” medical reports said, leaving it hanging by a frayed ligament and a five-inch flap of skin. Osiel was rushed to Mercy Medical Center, where surgeons amputated his lower leg.Back at the plant, Osiel’s supervisors hurriedly demanded workers’ identification papers. Technically, Osiel worked for Case Farms’ closely affiliated sanitation contractor, and suddenly the bosses seemed to care about immigration status. Within days, Osiel and several others—all underage and undocumented—were fired.Though Case Farms isn’t a household name, you’ve probably eaten its chicken. Each year, it produces nearly a billion pounds for customers such as Kentucky Fried Chicken, Popeyes, and Taco Bell. Boar’s Head sells its chicken as deli meat in supermarkets. Since 2011, the U.S. government has purchased nearly seventeen million dollars’ worth of Case Farms chicken, mostly for the federal school-lunch program.Case Farms plants are among the most dangerous workplaces in America. In 2015 alone, federal workplace-safety inspectors fined the company nearly two million dollars, and in the past seven years it has been cited for two hundred and forty violations. That’s more than any other company in the poultry industry except Tyson Foods, which has more than thirty times as many employees. David Michaels, the former head of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (osha), called Case Farms “an outrageously dangerous place to work.” Four years before Osiel lost his leg, Michaels’s inspectors had seen Case Farms employees standing on top of machines to sanitize them and warned the company that someone would get hurt. Just a week before Osiel’s accident, an inspector noted in a report that Case Farms had repeatedly taken advantage of loopholes in the law and given the agency false information. “The company has a twenty-five-year track record of failing to comply with federal workplace-safety standards,” Michaels said.Case Farms has built its business by recruiting some of the world’s most vulnerable immigrants, who endure harsh and at times illegal conditions that few Americans would put up with. When these workers have fought for higher pay and better conditions, the company has used their immigration status to get rid of vocal workers, avoid paying for injuries, and quash dissent. Thirty years ago, Congress passed an immigration law mandating fines and even jail time for employers who hire unauthorized workers, but trivial penalties and weak enforcement have allowed employers to evade responsibility. Under President Obama, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agreed not to investigate workers during labor disputes. Advocates worry that President Trump, whose Administration has targeted unauthorized immigrants, will scrap those agreements, emboldening employers to simply call ice anytime workers complain.

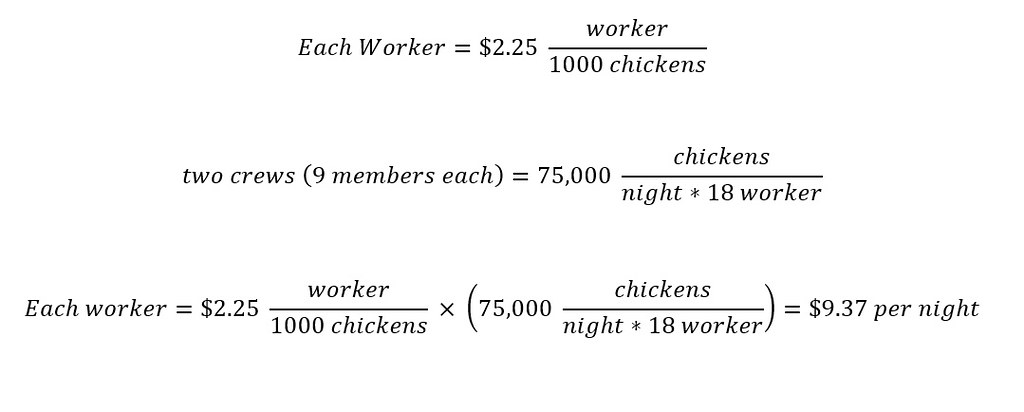

Workers who were interviewed in the article said that the pay to catch chickens per night was around $2.25 per thousand chickens. Two crews (each with nine workers) could gather 75,000 chickens in a single night. With those two numerical figures, the following math shows how much each worker brings home a night:

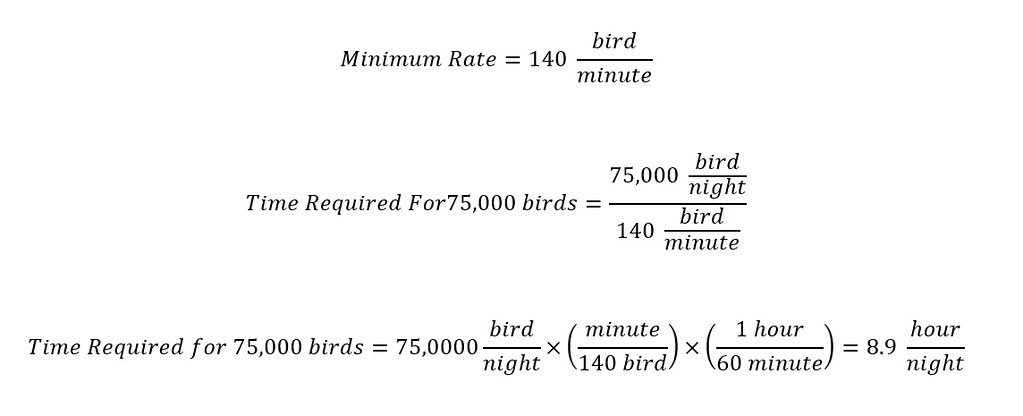

Oh My Goodness, what a rip off. For the environment in which these workers are exposed to, this is outrageous. Who would work in such conditions in their right mind? Unfortunately, the only workers who would take work are those who are desperate. Now, take into account that the 75,000 chickens need to be processed on a line running at a speed of 140 birds per minute.

Each worker gets around $9 per night to round up thousands of chickens in hazardous and infected conditions (feces, disease ridden cages). Furthermore, with the rate listed in the initial letter at a safe speed, processing 75,000 chickens with a single processing line would take 8.9 hours. Just over an 8 hour shift. Interesting enough, according to Michael Grabell's reporting, a large farm like Case farm runs their lines at a speed of 40 birds per minute. WOW!

Why then do chicken plants want to increase their processing speeds beyond 140 birds per minute?

Conclusion...

Something is not right here in the current negotiations. A large farm is operating a single processing line at a speed of 40 birds per minute. Quite possible is that the author misquoted the speed of Case Farm processing line speeds. When the minimum is set at 140 birds per minute, 75,000 birds can be processed in a single 8 hour shift.

What is ludicrous and inhumane to me is reading about workers being restricted from using the restroom. Some of the workers interviewed by Michael Grabell literally wore 'diapers' while working the processing line. Is that even sanitary? What would OSHA think about these conditions? OSHA stands for Occupation of Safety and Health Agency. Furthermore, a pregnant worker was denied the possibility to use the restroom on a 8 hr shift. What kind of businesses run their operations like this?

The take home message is that, our demand is motivating inhumane conditions. Of course, in any business, inhumane conditions can be influenced by the 'bottom line' (i.e. profits). If anyone see injustices like these reported in the article or sought changes to an existing line which are illegal, they should be compelled to speak up. No one deserves to work in inhumane conditions like those described above. Workers should be able to run a processing line at a maximum speed of 140 birds per minute -- possibly even a little less -- to avoid injuries. Businesses should take into account employee health rather than possible profits.

No comments:

Post a Comment